I’d like to tell the story of my career path, which appears, in hindsight to be driven mostly by happenstance rather than by some plan, with many frustrations leading to deviations along the way. My parents wanted me to be a doctor. Since my father was a dentist, he would have loved that one of his sons had decided to follow his career path, but none of us did, and I never even considered it a possibility. I thought in my early teens that I wanted to be a veterinarian, considering how much I loved animals of all kinds; however, when I went away to college, to follow a pre-medical study program, I really didn’t know what I wanted to do. Though being a medical doctor was on my list, I had no clarity that this was my future. In fact, when it came to applying to medical school in my junior year, developing a relationship with my first girlfriend, who would eventually become my wife, seemed more important to me.

My Initial Career Direction

I graduated from college with no clear direction except that I was interested in neuropsychopharmacology. My interest in neuropsychopharmacology was peeked by a book that I read in the early 70’s written by Floyd Bloom about Neuropsychopharmacology. (This book is presently out of print, and I can’t find a reference for it, but see Introduction to Neuropsychopharmacology1 which may be the current version of the same book.) After reading this book I took a course at the University of Pittsburgh in Physiological Psychology, which was about the connection between brain function and behavior, particularly eating and drinking behavior. This interest eventually motivated me to pursue graduate school in neuropsychopharmacology and the only places I could pursue this interest were in specific psychology or pharmacology departments, many to which I applied.

I was accepted into pharmacology at the University of Minnesota, which had two people with interest in fields related to neuro-psychopharmacology, I ended up being mentored by Akira E. Takemori, who was interested in the biochemical basis of opiate action, addiction and withdrawal.

My focus became characterizing two compounds – a long-acting opioid agonist and antagonist pair – which Takemori and his medicinal chemistry collaborator, Phillip Portoghese had developed. I had to characterize these compounds as covalently binding to the opioid receptor, as documented in my papers published in Science2 and the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics3. Once this characterization was completed, I spent about six months using them to purify that opioid receptor.4 For this work I received the 1980 Bacaner Award from the Minnesota Medical Foundation for the best pharmacology thesis among at least six other theses completed the previous year. My research was considered a classical work, in characterizing a receptor alkylating agent using state-of-the-art receptor binding technology in combination with traditional physiological characterization methods. The use of this to purify the opiate receptor was the icing on the cake. The Award Committee also was impressed with the quality of the writing in the thesis, not usual for medical research theses.

Postdoctoral Research Stimulating a Direction Change

For my postdoctoral work, rather than moving from Minneapolis, Minnesota to work in a laboratory where I could be at the cutting edge of opioid receptor research, in particular, I chose, in the summer, to stay in the Twin Cities area so my first wife could complete her degree at the University of Minnesota. In September 1979 I started work in the Psychiatry Research Laboratory at the St. Paul-Ramsey Medical Center, St. Paul, Minnesota with William Frey II and Susan Nicol, who were both trained molecular pharmacologists. I would stay in this position until April 1982.

My postdoctoral sponsors were willing to allow me to study the relationship between opioids and cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP, their specialty. This research did not develop into a program for study, so I switched to work on another opportunity: a constituent of brain homogenates that stimulated GTPase activity. This research pursuit also did not yield fruit, so by late 1981 my career in molecular pharmacology was sputtering to a halt, and while Frey allowed me to support his Alzheimer’s biobanking project, he was expecting me to move on.

My Initial Search for Pharmaceutical Industry Jobs

In early 1982, I began to pursue job opportunities in research in the pharmaceutical industry by sending my resume to a number of companies, and eventually getting an interview with McNeil Pharmaceutical, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, thanks to the help of a colleague from Takemori’s lab who was now working at McNeil. I did not get this position, nor did I get any other opportunity to which I applied in the pharmaceutical industry, and I know that I applied to several. (See below “My Continuing Search for Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industry Jobs”.) Challenges during my postdoctoral years, with no publications except one authored by one of my sponsors, Susan Nicols about cGMP and cAMP stability in human brain tissue,5 may have made it difficult for me to move on with a research career. In addition, I was developing interests in management.

The Career Change Move

At the same time that I was pursuing pharmaceutical jobs in 1982, I became very interested in Genentech’s biotech efforts which were at the top of the science news at the time. With thoughts of going to a graduate business program, I had been taking courses in economics and reading business magazines, particularly those articles about the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. Furthermore, I became interested in working with some friends, one a co-worker in my postdoctoral laboratory, on a passive solar energy unit construction company, helping them to write a business plan and even making a small $1000 investment, which the company used to build a prototype. These activities convinced me to pursue a masters in business administration, so I prior to leaving my postdoctoral position and I applied to top business schools, thinking that, if I couldn’t get into a top school, then it was not worth going. In early summer 1982 I got placed on the waiting list of the MIT Sloan School of Management, driving my decision to move to the Boston area and find a job there, if MIT did not accept me. However, before leaving Minnesota in July I got an acceptance letter from MIT, and so I moved to a house in Somerville, Massachusetts where I could commute to business school for two years.

Considering Technology Startups & Venture Capital

In the early 1980’s Boston was at the center of the personal computer revolution shortly after I had purchased my own personal computer in 1981, an Apple II+ (on which I wrote my business school application letters), and around the time that IBM had come on the market with the IBM PC. This created opportunities for entrepreneurial MIT, Harvard and other Boston college graduates to produce hardware, software and services that would enhance the power of these computers. The most significant of the resulting companies being Lotus 1-2-3, mimicking on the IBM PC the VisiCalc spreadsheet software that I was using on an Apple II+ Computer for financial modeling and other structured uses.

After my first year at MIT my future master’s thesis advisor, Edward Roberts helped me get an internship with his startup venture capital company, Zero Stage Capital. In this role I hoped to have an opportunity to plug into biotechnology startups; however, I naturally ended up finding most of my time spent on evaluating dozens of business plans about personal computer hardware, software and service companies.

I was extremely intrigued by these startup companies, and really enjoyed working from an investor perspective, evaluating each of these opportunities. This summer meant I had found what I wanted to do: venture capital, though I would have preferred to work in venture capital evaluating biotechnology companies. I eventually discovered that without any pharmaceutical or computer industry experience, and in particular, experience with companies as they went public, the venture capital industry had little interest in my applications, though I certainly tried. I also continued to try to get a position in the pharmaceutical industry. (See below ‘My Continuing Search for Pharmaceutical or Biotechnology Industry Jobs’.)

Metroview, My First Startup Company after MIT

During my work with Zero Stage Capital I learned about and met the founders of a service called Delphi, including Wes Kussmaul, and their company, General Videotex Corporation, having read their business plan and considered it as an investment for Zero Stage Capital. I was intrigued by this graphical online service capability called videotex, and the development of this technology by the pre-breakup AT&T. As a result I decided to do my master’s thesis on Joint Ventures in the Cable and Videotex Industries, doing it jointly with another MIT Sloan Student, Mark Harsch.6 This work allowed Harsch and me to meet leaders in the cable and videotex industries, including Samuel Berkman at AT&T who was leading various efforts to develop the videotex industry in the U.S.A.

Upon graduating from MIT, a conversation with Berkman resulted in an agreement that we would put together a business plan to create MetroView Corporation, a company developing city-based videotex networks providing information kiosks with ticketing and advertising capabilities. Supported by a small inheritance from my paternal uncle, Francis Caruso, I moved to New Jersey and began working with Berkman on a business plan for MetroView, and developed relationships with (1) a legal firm, once the legal firm for Lotus Development Corporation, with extensive experience in the venture capital industry, and which eventually introduced us to a number of venture capitalists; and (2) an accounting firm, Arthur Anderson & Company, who also would help us develop our relationships with investors and suppliers. Berkman built the team of expert marketing and operations people, and we both identified a financial man with experience taking a company public. The accounting and legal professionals critiqued the business plan, and put together a structure that was fundable and scalable. They then shopped our plan with their VC contacts.

Had videotex been successful at any of the many companies that were developing videotex services in the mid-80’s, including Knight-Ridder/AT&T in Southern Florida, Times Mirror/InfoMart in Southern California, and many others, we would have had our funds for development of networks in a number of cities in the U.S., but videotex never succeeded. While searching for investors in MetroView, I found in spring 1985 a new partner in Ira Samuels who wanted to help because he had developed a phonemeter technology for building a network of private pay phones, a developing business model at the time when AT&T was being broken up and their pay phone business was becoming a competitive opportunity.

Incutech, A Venture Capital Partnership Focused on Telecommunications

Samuels, an engineer and nephew of David Sarnoff of RCA fame, liked my MetroView business plan, which besides being better written than other plans he had seen, he was interested in adding it to the private payphone using his technology. However, when we met a non-compete limited him for another year from going down this path, so in the meantime, he proposed that we start a venture capital company to invest in technology companies. Around October 1985 Samuels agreed to pay me a minimum salary to work with him and his friend Ed Ladenheim, a project manager from Sperry Univac, as a partner in the company we formed called Incutech, which would consider investments in telecommunications companies. We then began developing plans for investing in various startups, and in one Chapter 11 reorganization opportunity. Thanks to his expertise in electrical engineering and structured systems analysis and Ed Ladenheim’s expertise in project management, I learned to apply new skills to the development of new products and businesses. This relationship had its starts and stops, as Samuels would rethink his strategy and business opportunities, and even his financial relationship with me.

ViewPhone, the Revival of MetroView

Around the spring of 1986 we started developing ViewPhone, a private pay telephone service which would implement both Samuels’ phonemeter and videotex technology. Furthermore, I would bring back Sam Berkman and many of the other team involved in MetroView as partners in ViewPhone. Through a relationship with Ed Francois at Fahnestock & Co., a significant investment bank on Wall Street, we built a partnership that eventually led to a best efforts offer to raise $20 M, but Samuels refused the money saying he didn’t want to spend five years developing another company without significant returns. At that point in late 1986 I decided this relationship with Samuels was not going anywhere, so I left to return to my search for full-time jobs.

Special Care, A Startup to Treat People with HIV/AIDS

After continued challenges finding new job opportunities (see My Continuing Search for Pharmaceutical or Biotechnology Industry Jobs below), I started thinking about a new venture that would provide capitated care to people with HIV infection, including people with AIDS. My previous connection with Ed Francois at Fahnestock encouraged me to go this route. Francois offered his services to connect me to people who could help develop the business plan and raise money. Here are a few of the numerous conversations I had resulting from our efforts:

- Joseph Califano, Jr., who was involved in the development of Medicare and Medicaid for Lyndon Johnson, and was also Secretary of Health and Human Services for President Jimmy Carter.

- The CEO of University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey who thought that people with AIDS would be dying in the streets because no one wanted to pay for their care.

- Several AIDS Care Specialists in New York City, one who met with me weekly to come up with a design for a care center focused on treating people with HIV infection.

- The Task Force on AIDS, Newark, New Jersey, made up of elected officials, community residents and leaders, health care workers, scientists and educators.

- The Secretary of Health for New Jersey who wanted to help, but had his political hands tied by the stigma around AIDS and HIV infection.

- The Executive Director and Founder of the Foundation for AIDS Research about how we might integrated our efforts with theirs.

Ed Francois eventually brought in a New Jersey real estate entrepreneur and a medical commodities trader to be on the team we were developing. In early 1988, this team wanted to buy a property in a depressed area of Newark, and bill it as an AIDS treatment center. I balked at this plan because I did not think it would increase the value of the property, which others argued as part of their strategy for getting a deal on the property. As a result, at the next board meeting, they wanted me off the board – but they were not shareholders, and I had controlling position relative to Francois, so I ended my relationship with them, and then got back to looking, maybe more seriously than ever before, for a job in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry.

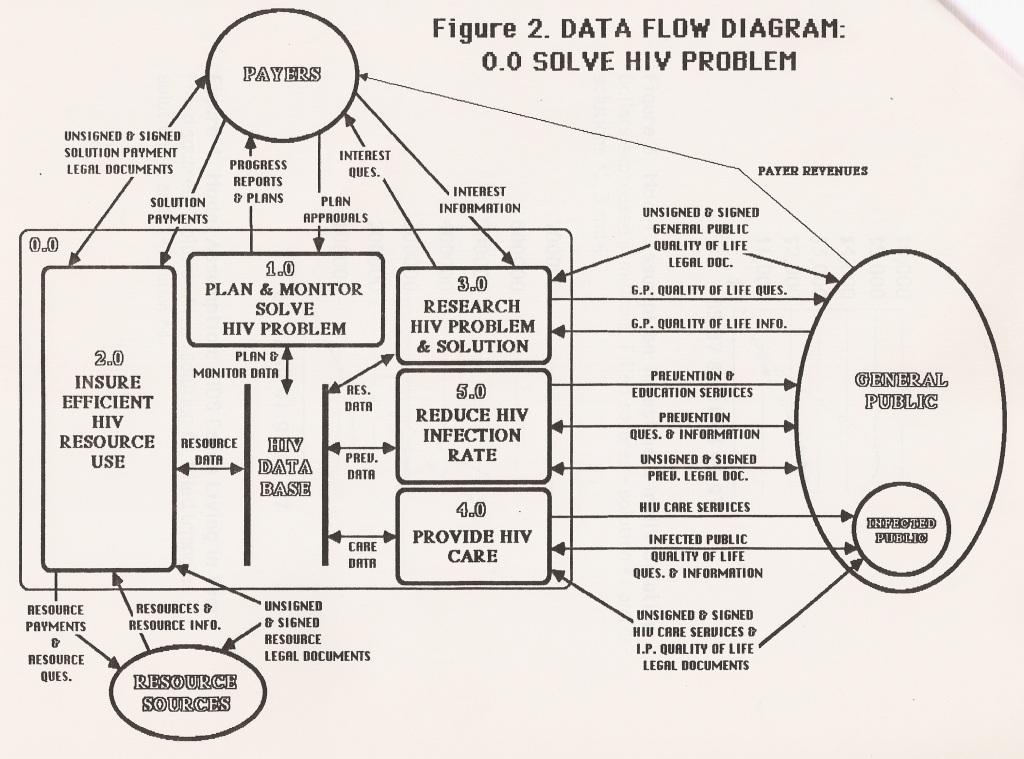

My efforts to analyze the HIV problem, stimulated me to write a manuscript called ‘A Structured Solution to the HIV Problem,’ which I submitted to Ed Yourdon, author and editor of many books about structured analysis. He was quite intrigued by my work, and introduced me to his publisher who decided that a book about this subject was not a good fit for any audience. I did get a chance to present my ideas on a locally broadcast TV network, and when I was there for the interview, I also had a chance to meet Ed Yourdon in person.

My Continuing Search for Pharmaceutical or Biotechnology Industry Jobs

My search for pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry jobs never really abated throughout this entire period, and increased substantially upon the termination of Special Care. These industries were always a direction that I thought would be good considering my doctorate and interest in pharmacology. Furthermore, every recruiter who had an interest in helping me encouraged such searches after they saw my resume. Obviously to them, someone with a doctorate in pharmacology and an MBA from MIT Sloan School should be able to get a job in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry. In total they must have spent a hundreds of hours talking to their clients about the career possibilities for someone with my background, and some may have gotten me in front of their clients for further discussion. I expect they were confused when each time they were hindered in finding me a job. Why would they fail? Here is my reasoning that I came to after pursuing every one of these positions multiple times within the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry:

- Drug Discovery Research Jobs. With two and a half years of unproductive research during my postdoctoral fellowship, I failed to be competitive with pharmacology researchers who had great success throughout their academic development, and once I went to business school, returning to the lab bench was out of the question, not only for the employer, but also for me, who did not want a lab job anyway or why would I have gone to business school?

- Drug Development Jobs. Though I eventually developed project management skills, and with my technical knowledge, I certainly would have been an asset in these positions; nonetheless, for project management positions, I competed with a large number of clinical research associates who wanted to take the next step and had years of experience in the industry; or for entry-level clinical research associate positions, I competed with people who had a bachelors of science right out of college who could convince the employer that they were going to stay around, i.e., I was told that I was either underqualified for project management jobs or overqualified for clinical research associate jobs.

- Sales, Marketing and Business Development Jobs. Here again, the combination of MBA and technical knowledge seemed appropriate for these openings; however, for marketing research and business development positions I competed with a large number of pharmaceutical sales representatives who wanted to take the next step and had years of experience in the industry; or for entry-level sales representative positions I competed with people who had a bachelors of science right out of college and could convince the employer that they were going to stay around, i.e., I was told that I was either underqualified for marketing research or business development positions or overqualified for sales representative jobs.

There even were recruiters within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies that were convinced that I could contribute substantially to their company. One recruiter comes to mind at Merck, where human resources played a major role in identifying people for positions, yet even she was unable to find something to which I was not either underqualified because I did not have the years of pharmaceutical experience the hiring manager preferred, or overqualified because I would not stick around long enough in the position considering that the investment in my training would not have been worth the effort.

I applied to every major pharmaceutical company and had interviews with most of them in one or more positions for research, development project manager, clinical research associate, marketing research, business development, international market development, and even sales representative. I got close to getting some of these positions, but never got to work in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry, which still surprises everyone who sees my resume.

If I wanted to work in the pharmaceutical industry, I would have done better to apply to entry-level positions right out of college (and then gone into a Ph.D. or MBA program). I don’t think my research skills ever could have gotten me into a research position, unless my choice for a postdoctoral position got me into a laboratory where I could have been more productive and visible to the pharmaceutical industry.

Where the Search for Real Jobs Took Me

In the fall of 1988, needing a job that paid a salary after my recovery from a fractured neck of the femur (a hip injury that I got while water skiing in Canada at an family reunion), and unable to land a job in the pharmaceutical or biotechnology industry, no matter how hard I tried, I turned to my knowledge of structured systems analysis and project management. I also went into New York to take an evening course in systems analysis, though I could have taught that course, and, in fact, in a later incarnation I actually did teach a Systems Analysis and Project Management course online for the North Carolina Central University. The major consulting companies, in particular, Coopers and Lybrand, one of the Big Eight Accounting and Consulting Firms in the 1980s, showed interest in my systems analysis and project management skills. In fact, a Coopers recruiter had me interview with one of their lead systems analysts, and I was told that this interviewer thought I was the best analyst with whom she had ever spoken. However, Coopers acted too slowly in offering me a job, and so I accepted a position as a Quality Assurance Project Manager with the Financial Systems Division of National Computer Systems. So in January 1989 I started with my first real job since I left my postdoctoral position in early 1982, but this was a job working on financial systems. I was conflicted working in a field which had nothing to do with my training in molecular pharmacology. I would struggle with this conflict for almost 15 years when I finally ended up working in program development in the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine at Virginia Tech.

My Early Project Management Career

The job I had accepted was with National Computer Systems, as part of the FUNDEX development team in Parsippany, New Jersey. In this role I spent a fruitful year learning about software development and the latest Windows 2.0 tools for project management, as well as how to organize teams to schedule and complete complex tasks, while not knowing much about those tasks. A consultant introduced me to Windows 2.0 and associated PC-based applications at a time when no one was using Windows on a PC. People either were using windows-based applications on an Apple Macintosh, as I was at home having upgraded from my Apple II+ in 1985, or they were using PC DOS applications, with which I had some experience while working at Incutech. While others on the FUNDEX team were given the responsibility of designing and coding the upgrades of a mutual fund transaction processing system for the single customer for this project, Pioneer Funds, I was told to prepare for the quality assurance phase during which we would need to begin tracking the software configuration versions.

Software Project Manager

First, I developed a project management plan using a PC DOS-based application. I estimated project completion around mid-September. Simultaneously, with help from a developer, I built a bug tracking tool linked to a Digital Equipment software configuration system. My structured project management-software configuration approach (see figure) involved organizing designers and developers into teams responsible for parts of the deliverables. Then I would work closely with the individuals who would be project managers, designers and testers for their part (1) to develop a plan for completing their deliverables, (2) to build and keep the system updated with progress information, (3) to test the software when it was delivered from the programmer, (4) to file bug fix requests to bring the software up to the requirements originally set in the design, and (5) to work with the programmer to complete priority bug fix requests. My supervisor was responsible for prioritizing the fixes until he thought the product was ready for system test – which involved testing all parts together at once, using a broader test of all functionality of the system resulting in more bug fix requests and their prioritization until the software was done to specification. Then the software was ready to go to the customer for user-acceptance testing. This was all completed as per my original project plan, and then everything fell apart for FUNDEX because the customer had many more requirements, and NCS could not meet these in the required timeframe, so the result, by November was that NCS shut down FUNDEX operations and took a $5 M write-off.

Starting a Project Leader Position

My efforts with the FUNDEX team had proved my worth to NCS and, though everyone but the secretary got laid off, the director of the NCS TrustMaster Product Lines, Walter Milzarek in Boston asked me to help him with his financial plan, and I ended up in his office the next week in early December. A month later, I had a project leader position in Boston with the NCS TrustMaster team.

Initially, I worked with Milzarek to develop a model and forecast for his $18 M budget. That work was short lasting, but after NCS had lost $5 M from the FUNDEX write-off, the division and company had been in a hiring freeze, so my full-time employment required a double sign-off by both the division VP and the NCS CEO. The results of my efforts were enough to get the transfer to Boston, and also meant that for the next four years I would be managing budgets, with annual efforts and monthly reporting for Brian LeBlanc the controller of the division. This gave me the opportunity to learn about budgeting and the use of Excel macros to build a large budget systems for the division.

Developing Project Management Methodology

My primary activity for the next three years was building a project management methodology for three product lines: two TrustMaster lines, and a new product line in development called Ultrust. For this I had a number of activities:

- Trained staff in project management by identifying a training program endorsed by NCS for this purpose and then organizing the training.

- Identified a project management software tool, which middle managers agreed on using.

- Developed a structured project management methodology with the staff working on the smaller of the two TrustMaster product lines, defining team roles, working with those team members to define a project plan template, building the first project plan for a future release, developing a change control process, and then overseeing the implementation of the methodology in a pilot release project.

- Scaled the project management methodology for the larger TrustMaster product line.

- Documented the project management methodology using a unique structured systems analysis approach to policies and procedures documentation.

- Developed and implemented an MS Project-based project management methodology for the Ultrust product line that included building unit teams, printing and posting monthly a large PERT chart showing progress of the Ultrust project, and teaching the technical project manager of Ultrust how to use this methodology to better manage his projects.

I was also called on to turnaround a failing contract relationship with the second customer of Ultrust. For this effort, I went to the customer site and worked with their project manager to build a project plan for implementing Ultrust. When I arrived, the customer was filing a suit that claimed that NCS had reneged on it’s contract, but within a month, they dropped the proceedings as the result of my efforts.

I presented my structured project management methodology at an Annual Project Management Institute meeting in 1992. I was surprised when I started studying in 2009 for my Project Management Professional (PMP) Certification because the processes outlined in the Project Management Body of Knowledge looked very much like my structured project management methodology (see figures above and to left). I did not become a certified PMP until 2010, when I needed the certification for pursuing contracting jobs in the Federal Government, but my experience at NCS had prepared me for success at this effort.

A number of years after I left NCS, one of the people with whom I had worked on the project management methodology and now at Fidelity, told me that when she had worked with me at NCS she learned how to do project management the right way. Not bad considering I didn’t know what I was doing joining a large software development project.

A Stint in Application Program Development

In 1993 I became very interested in the use of Lotus Notes for the development of collaborative business applications. I was looking for a tool to help with management of sales forecasts, and I found Lotus Notes could allow sales people to input forecasts for each of their customers or potential customers, and that this information could roll up into a geographic and division sales forecast. In the early 1990’s Lotus Notes was providing a means for users to have a local data store on which they could work even when disconnected from the networked data store, say, for instance, while they were on a plane. These local data stores would ‘replicate’ with the networked data store when the connection was possible.

This was a few years before the Internet was in popular use. Notes was transforming collaboration so much that Fortune Magazine said that, “Without question, Notes already is the most important business software tool in the new era of client-server PC computing.”8 (Yes, Lotus Notes later died, and I blame that on IBM’s take over of Lotus with the idea that they were going to do a better job with Lotus Notes. It’s interesting that the original developer of Lotus Notes, Ray Ozzie, later moved to Microsoft to develop Microsoft SharePoint which looks a lot like Lotus Notes from an application developers perspective.)

So I convinced my managers at NCS, particularly the sales organization, to allow me to set up and administer a Lotus Notes Server and train their sales force in the use of the application. I subsequently built a Notes network of 30 users. I developed various applications that the sales force found useful, including a product information database and a tool for sales forecasting. International Data Corporation studied this sales forecasting application for the ‘Lotus Notes Agent of Change Study, 1994’ which showed that proper implementation would generate a return on investment of 176%.

When NCS decided to layoff about 80 employees because they could not turn Ultrust into a system for Bankers Trust or any other trust company, I left among those laid off, though they gave me continuing consulting work on the budget and financial reporting system that I had build. After the layoff, I soon found myself consulting in Lotus Notes application development for NyNex, and several other companies. I also joined my next startup.

Corporate Image Software – The Lotus Notes Addon Company

After being laid off by NCS in 1994, the year my son was born, my search for full-time work generated two opportunities, one with a telecommunications consulting company and the other a chance to try again to build a company, Corporate Image Software, that would take advantage of the developing opportunities in Lotus Notes addons. I met the founder of the startup at a local meeting in the Boston area, and found reason to talk about how I could help market and sell an addon for Lotus Notes that allowed incorporation of graphics into Lotus Notes applications. I decided to give this a try and though we were able to develop an application and its package, as well as build sales to about $3,000 per month, after five months it was not enough to convince me that we had a potential successful business, so I came to an agreement with the founder and left. That’s when I began consulting in Lotus Notes application development until I moved to Southwest Virginia to minimize dealings with my x-wife and begin a new relationship, regrettably leaving my son behind. This change led to my first program development job at Virginia Tech in Southwest Virginia.

Starting a Program Development Career

Some of the following has been already covered in Thoughts About My Academic Experience which at Virginia Tech and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was all about my academic career mostly in research program development. Here I am going to provide more details about my career path while at these institutions.

The job I got at Virginia Tech in the Office of the Vice Provost for Research and Development working for the Associate Vice Provost for Program Development, was as Industry Program Development Specialist. The salary was a 30% cut from what I had made in Boston, but then the cost of living was substantially lower in Blacksburg, Virginia, and at least it was a regular salary compared to consulting income. Salary has always been how I related myself to other graduates of MIT Sloan, and it was certainly lower than any of my colleagues who were still working at that time.

The position was partially funded by the Virginia Center for Innovative Technology (CIT), with the objective of working with the professionals at CIT around the Commonwealth of Virginia to assist in connecting companies to faculty at Virginia Tech. That meant my job would be mostly focused on engineering faculty, though there were some connections to computer science and biotechnology faculty, and companies interested in their expertise. So I built skills and tools for generating interest in Virginia Tech faculty, and whenever some CIT staff or a company wanted help, I was the resource they could use to set up meetings with faculty. My efforts also included three years of working with the College of Engineering to hold an Industry-Academic Event Day at which industry representatives visited the Virginia Tech campus to see presentations and join lab tours held by Engineering faculty. I also sponsored an SBIR Industry Day at Virginia Tech that included dinner presentations by the Virginia Governor and his Secretary of Technology. I soon became rather bored with organizing meetings, and trying to get faculty and companies to work together – which was never easy. So it wasn’t long before I started looking again for new jobs, primarily sending resumes out and having little, if any success. I felt trapped, and did not know any good means of moving on.

Success with Grant Development

A number of years into this position I also took advantage of a funding opportunity offered by CIT to fund ‘Technology Innovation Centers’ (TICs). With my knowledge of the strengths of Virginia Tech in information technology, including computer science, wireless technology, cellular technology, and computer networking, as well as my connections around the Commonwealth of Virginia, I was able to put together a partnership of three other Virginia universities, to win a $2 M grant from CIT for an Internet Technology Innovation Center. The Internet was hot in the late 1990’s and so this was a sure thing from the moment I started putting it together, and that was a lot of fun considering all the connections I could make who were also going to benefit from that connection because they would get some of these funds. This was the key to being successful as a program developer: bring funds to faculty and the University.

Success Building Major University Initiative

Then I started finding ways that I could develop partnerships with industry and faculty to pursue government funding, both Federal and State funding. When CIT decided to no longer fund my position, I was able to focus on such partnerships. One of the key opportunities in which I was involved, was the Food, Nutrition and Health Cross-Cutting Initiative (FNHCCI), a program that had been developing for several years, and had survived other cross-cutting initiatives that had originally been created by Provost Peggy S. Meszaros (1995-2000) as a major University-wide teaching, research and outreach strategic initiative. I was asked to support the committee thinking about how to move forward with the FNHCCI, particularly to help them build connections to industry, and so I did this and more, bringing to Virginia Tech for three industry steering committee meetings, representatives from Cargill, Syngenta, Monsanto, Tysons, Roche Vitamins, Procter & Gamble, and other companies representing ‘field-to-fork’ industries, as well as the representatives from government including the USDA and the FDA.

My work resulted in the development of an overall research strategy that involved some 70 faculty from five different Virginia Tech colleges, as well as the Cooperative Extension and Agricultural Experiment Stations. The plan itself was an ingenious melding of a broad set of research interests, from genetic engineering of better plants and animals, to research into how to get product from field to fork, while maintaining integrity of the product and its differentiation from other products. Many academic disciplines were involved including biotechnology, animal and poultry sciences, veterinary medicine, agricultural economics, food science, nutrition, and even agricultural systems engineering, and the opportunity to bring the science to the farmers, food-related businesses, and food consumers in Virginia was enhanced by the involvement of the Virginia Tech Extension Program which had employees, agriculture and political connections spread throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The last Steering Committee Meeting of three was held in Northern Virginia and, besides leaders from Virginia Tech, like the new Provost Mark McNamee (2001-2015), attendees included Federal government representatives and experts, such as Lester Crawford, then a candidate for the Commissioner of the Food & Drug Administration, as well as a past USDA Administrator of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service who would eventually be made the Director of the Virginia Tech Food, Nutrition & Health Institute (FNHI). At the end of this meeting, during which we passed out shirts with the logo above, Provost McNamee made a presentation summarizing what he got from the meeting, and he agreed this had to be one of the two top initiatives of Virginia Tech, not a small feat for an institution with dozens of competing major initiatives. The Provost eventually convinced his superiors of the importance of creating an FNHI, and the President wrote a letter to the Governor of Virginia asking for his support for major funding, as part of Virginia Tech’s effort to raise funding for its Five Year Plan for the Virginia Extension Service. I worked with leadership of the putative FNHI to build support throughout the State for this Five Year Plan, by recruiting the 1000+ Full Time Equivalents in the Extension Program to do presentations across the Commonwealth of Virginia.

A Career Move into Biomedicine Research Program Development

Had it not been for a fiscal shortfall in the year that we submitted the Cooperative Extension Service Five Year Plan, we would have likely raised more funds for Extension than they had ever raised in the past, but instead the Virginia Legislature asked for cuts, and I ended up moving to the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine (VMRCVM), where one of the deans who was involved in the FNHI effort, and who was impressed with my involvement in it, Dean Peter Eyre, wanted me to join his organization.

In VMRCVM I became the Director of Research Initiatives under the Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Studies, Gerhardt Schurig who had experience and interest in building a strong infectious disease program at Virginia Tech. In fact Schurig was the lead of a committee formed by Provost James R. Bohland (interim, 2000-01) to investigate an Infectious Disease Initiative, which was another effort that I supported while in the Office of the Vice Provost for Research & Graduate Studies. When I joined VMRCVM I immediately started to work on, and eventually obtained funding for:

- An infectious disease research laboratory with an BSL-3 animal facility, and

- Two research training grants for (1) postdoctoral veterinarians interested in doing infectious disease and immunology research, and (2) veterinary students interested in considering a research career.

Total funding of $8 M (eventually increased to $10 M)9 for the Infectious Disease Research Facility (IDRF) came only from the State and the Virginia Tech Foundation, with no funds from NIH which had stopped their facility funding that year, but it was enough to build a scaled-down IDRF that now stands on the VMRCVM grounds opening in November 2011.9 While the two training grants, the first of these (NIH T32 and T35 awards) obtained at Virginia Tech, were for a total of about $850,000. I then spent the next years implementing the plans we had put in place for these funds.

Adding IT Project Management to Program Development Career

Two years prior to leaving Virginia Tech, I was warned that when a budget cut came, that my position was likely to be terminated. Mostly because a number of faculty in VMRCVM thought that funds for my position were not used as effectively as they could be used for a faculty member who would lessen teaching loads and allow research faculty to generate more research dollars, even though I was helping faculty raise research dollars for the College, as well as developing a strategic alignment towards research areas with funding potential. I was given one year notice that I would be terminated in August 2008. Though I was always looking for ways to move on from Virginia Tech, my last two years there were quite focused on finding a new job – from this search on, it always took me at least two years to find a new full-time position, and after the last two year search, I retired without finding employment.

My work while at VMRCVM with the NCI caBIG (see experience with medical data networks for research uses) and the Clinical & Translational Science Award programs generated a number of on-site interviews, including for positions at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Washington University in Saint Louis, University of Michigan, University of Vermont, Becton Dickenson, and others; however, I failed to have adequate biomedical informatics experience to obtain any one of these positions. I left Virginia Tech on 14 August 2008 without a job, but with plenty of new job search activity.

Moving to a Career in Government Contracting

A recruiter at SRA International must have spotted something in my resume and the SRA program manager (a Virginia Tech graduate) for a contract with the NIH Center for Information Technology (NIH CIT) had a requirement for someone to both serve in a project management role and to help the contractor find new sources of funds at NIH. My experience with NCI, through my work with caBIG, also was of interest to SRA because they had other NCI contracts related to caBIG. They also liked that I could both manage IT projects and develop research programs, and their NIH CIT client liked me too, so I got the job and moved to Maryland to work at NIH. However, the client’s needs changed with time, and he eventually decided that he only wanted a part-time project manager, and that he would take care of his own program development, so in a little more than a year, I was off that project, and during a transition period of five months, SRA could not find me an alternative place, so again I left a job without further employment. Another two years were required before I found my next full-time job.

Developing My Own Program – The BITT

As I looked for new full-time job opportunities, I developed the Biomedical Informatics Think Tank (BITT; see experience with medical data networks for research uses). The leaders of BITT thought that we could tag onto CIO-SP3 proposals, a 10- year Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract opportunity, which, if won, gave a company a license to develop and bid health-related IT projects in the Federal Government, including the NIH and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), two of the biggest contracting agencies in the Department of Health and Human Services. BITT was included in proposals in response to both the large and small company requests for proposal (RFPs), but neither of these companies won an award. Separately I was included as a program manager on a small company award, and it got funded after I had accepted a new position at UNC Chapel Hill in late 2011, so I withdrew from the company’s efforts to build funded projects on the CIO-SP3 award.

Another Startup – Quantal Semantics

Several of the members of BITT also decided to pursue development of a Universal Exchange Language in response to the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) titled “Realizing the Full Potential of Health Information Technology to Improve Healthcare for Americans: The Path Forward”.

As a result we created the Quantal Universal Exchange Language (QuantalUEL) and then three of us became partners in a startup we created called Quantal Semantics, more on this can be found in experience with medical data networks for research uses. Once I got the position at UNC Chapel Hill, I had no further interest in pursuing this business which I did not think had a future that could provide me with significant support.

Mixing of Program Development, Business Development & Project Management

In my ongoing search for job opportunities I found a position at UNC Chapel Hill which involved building a partnership between their School of Information and Library Science (SILS) and RTI International’s Center for the Advancement of Health Information Technology (CAHIT). Both organizations saw logic in a partnership and needed someone to drive its development. With my experience in government contracting, academic research program development, and biomedical informatics, this seemed a good fit for all parties involved, so in January 2012 I moved to the Research Triangle to accept the position. I immediately got working on an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) proposal for Personal Health Information Management, which included both UNC SILS and RTI, but after two attempts at funding we were unable to obtain an award.11 However, my primary effort included developing two opportunities addressed in experience with medical data networks for research uses:

- UNC-RTI Self-Generated Health Information Exchange

- PCORI-Funded PCORnet Patient-Powered Research Network

The Self-Generated Health Information Exchange led to a partnership with Promantus which, when I left UNC Chapel Hill, negotiated the rights to the SGHIx network so they could further market it. SGHIx.org is still up on the Internet, so I assume it has had some value for Promantus.

Merging Venture Capital, Asset Management and Pharmaceuticals

While at UNC Chapel Hill I met again with a past friend and a serial entrepreneur with whom I worked previously at Virginia Tech to plan a venture capital company that would obtain funds from alumni to invest in businesses being spun off by Virginia Tech faculty. This plan never made it past the review of the Virginia Tech CFO, but it was the start of a relationship that would become another plan for a company that developed pharmaceutical assets. We called this venture PreClinix, because it would take drugs through preclinical development to phase I, II or III clinical trials before selling off the assets to a firm with pharmaceutical marketing muscle. We conceived of an organization that would fund shells that owned the assets and would receive investment for their development, but the development would be done by a management company that had the expertise to develop pharmaceutical products. As the product got developed towards sale, some human resources might become part of that business; however, upon sale, negotiations would determine whether human resources would be included with the sale of the pharmaceutical asset, or whether those resources would remain with the management company. Again, I had to back out of this venture, as I was restricted from such efforts once I joined PCORI.

Program Management at Technical Frontiers and PCORI

Also while at UNC Chapel Hill I got involved in managing an NIH contract for Technical Frontiers Inc (TFI). My supervisor, Dean of the SILS Gary Marchionini, agreed to give me one day per week to manage an NIH contract for TFI. I had interviewed with TFI when considering a move back to the DC area, which was the location of my fiancé, until she got laid off and could then move to the Research Triangle to marry me in July 2013.

The TFI contract was with the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) to manage a team supporting the Clinical Trial Database (CTDB) that was used throughout the NIH. I joined the team and shortly after reorganized it, letting go of several people and hiring a project manager, and then, with time, building the staff up again. With my help TFI won a recompete for the contract which more than doubled its value to TFI. I left as program manager at TFI when I joined PCORI.

At PCORI I also took on the role of program manager in June 2015, responsible for the operations of the Research Infrastructure organization that was building the PCORnet program (see experience with medical data networks for research uses).

I consider my job at PCORI as the peak of my career. At PCORI I was helping manage a program with a total budget exceeding $425 M over five years, about 18% of the total ten year PCORI budget of $2.4 B. My salary was now more than three times what it was 20 years earlier when I joined Virginia Tech. Besides assisting with terminations, hirings, reorganization, and, especially the creation of a master contract structure with the PCORnet Coordinating Center which simplified oversight, and provided a mechanism for creating new task orders without having to redo an entire contract. I was disappointed when I was reorganized out of that position. I apparently had organized the operations so well, they no longer needed someone in my role, with the staff that I helped recruit and put into roles that efficiently managed operations, no longer needing my efforts.

Winding Down

I followed my PCORI work with a temporary project management role at the Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA, working with the same people at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care with whom I worked at PCORI as a component of the PCORnet Coordinating Center. I left this position when my employer found a project manager who asked for much less pay, since my salary requirements were higher following my experience at PCORI.

Then I again spent two years looking for my next position, now networking like I had never done before. During this time, I took on a major responsibility with the Mankind Project as the Community Coordinator for Northern Virginia, and obtained many rewards helping men connect, creating new events, getting men to step into their leadership, and showing myself my true strengths: organizing to bring communities together.

My efforts to find work during this time were interrupted when my wife found new work in Albany in 2019, and then again a few months later in the Greater Boston area. Though I got close to getting offers, when the COVID-19 Pandemic happened, once again it had been two years looking and now I was 67 years old, and thinking it was time to retire from this rollercoaster ride.

So here I am in retirement spending time writing in my blog http://tpcaruso.com.

In Retirement

Two major activities have kept me busy through the last three years in retirement:

- Moving to Australia to Support my Australian Wife’s Return to her Country

- Increasing my volunteer activities with the Mankind Project

Moving to Australia to Support my Australian Wife’s Return to her Country

I had known since meeting the women who would become my fourth wife, that she wanted to eventually move back to Australia, which was one component of my interest in this relationship. For fourteen years together in the U.S.A., I worked with her to plan the move. It wasn’t until her second job in the Boston area, when she was finally ready to move, with the hope that her company would move her since not only was it a period when everyone in her office was working from home, but also her colleagues were based all around the world. She had decided though that we would move regardless, but her company did eventually agree to allow her to keep her job in Australia. So this meant I spent much of 2022 planning, preparing and making this move. We landed in Australia on November 2, 2022, got all our shipment from the U.S.A. on December 30, 2022, obtained my Australian Permanent Residency in mid-March, and just purchased a car. We plan to finish renovations to my wife’s apartment that she owns in a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland, and then find a place in Queensland that will become our permanent home.

Increasing my volunteer activities with the Mankind Project

Upon deciding to retire in March 2020, my life decision was, ‘Now what do I do with my time?’. I found myself getting more and more involved in the Mankind Project, taking on first the Greater Boston Community Coordinator role in the New England Area of MKP USA, after having been the Northern Virginia Community Coordinator in the MidAtlantic Area of MKP USA. Then an NE Area leader and member of my Greater Boston Men’s Circle asked me to be a Weekend Coordinator for the May 2022 New Warrior Training Adventure (NWTA). I learned a lot about these weekends but two weeks before the start of the NWTA, the staff decided to cancel the training. At that point my focus was on moving as described above.

Once we moved to Australia, I immediately attended a Brother Dance at a Queensland NWTA in November, and then started attending two men’s circles on alternate weekends. Transportation has been a challenge, but public transportation is excellent in Brisbane, and men have always been willing to help drive me to or from events. Throughout the first three months I felt well supported by the elder community and other MKP leaders in the Queensland. This made it easy for me to step into the Secretary role for the Queensland Elder Body, and both the Staff Coordinator and Weekend Coordinator roles in the March NWTA. Most recently I have taken on the Training Coordinator for the July NWTA, and expect to do the Weekend Coordinator role on that weekend.

What I love most about my life in retirement, is the loving and supportive relationship I have with my wife, and the wonderful connections I am making as I become fully absorbed in Queensland, Australia culture. Not to mention how great the weather is here on most days.

Final Thoughts About My Career

Looking back on the entire path of my career, I’m amazed and intrigued, when before completing this project I was disappointed. My career took me in so many different directions, and wherever it took me, I did a good job. I did experience several peaks of performance in the process from:

- experiencing the ups and downs of an entrepreneur and venture capitalist,

- developing a project management methodology for three financial software product lines,

- creating a Lotus Notes Network in the early days of groupware even before the popularity of the Internet,

- building a Food, Nutrition & Health Institute at Virginia Tech,

- creating a novel Self-Generated Health Information Exchange concept and piloting that idea at UNC Chapel Hill,

- restructuring operations for the Research Infrastructure program at PCORI,

- building a connected Northern Virginia Community and the Greater Boston Community for the Mankind Project, to

- moving to Australia and becoming connected with the culture here through my full engagement with the Queensland Mankind Project.

My career wasn’t a traditional academic, industry or government career; it didn’t follow any discipline (i.e., pharmacology, computer science, etc.); and it had no functional evolution (i.e., specialist to project manager to director to vice president, etc. or postdoc to assistant professor to associate professor to professor to department head to dean, etc.). Though it did involve a clear interest in innovative thinking about organizations (structured project management teams, cross-disciplinary teams, tool-enhanced teams, complex teaching-research-service teams, cross-organizational boundary teams, etc.), and services (videotex, case management, groupware, research networks, community support, etc.). In all, I am proud of my career, as it was done bringing fun and joy, as well as achievement into my life and the life of others.

References

- Iversen, LL, FE Bloom, SD Iversen, and RH Roth. Introduction to Neuropsychopharmacology. Accessed April 11, 2021. https://www.goodreads.com/work/best_book/5947917-introduction-to-neuropsychopharmacology.

- Caruso TP, AE Takemori, DL Larson, PS Portoghese. Chloroxymorphamine, an opioid receptor site-directed alkylating agent having narcotic agonist activity. Science. 204(4390): 316-8, Apr 1979.

- Caruso TP, DL Larson, PS Portoghese, AE Takemori. Pharmacological studies with an alkylating narcotic agonist, chloroxymorphamine, and antagonist, chlornaltrexamine. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 213(3): 539-44, Jun 1980.

- Caruso TP, DL Larson, PS Portoghese, AE Takemori. Isolation of selective 3H-chlornaltrexamine-bound complexes, possible opioid receptor components in brains of mice. Life Sciences. 27(22): 2063-9, Dec 1980.

- Nicol SE, SE Senogles, TP Caruso, JJ Hudziak, JD McSwigan, WH Frey 2d. Postmortem stability of dopamine-sensitive adenylate cyclase, guanylate cyclase, ATPase, and GTPase in rat striatum. Journal of Neurochemistry. 37(6): 1535-9, Dec 1981.

- Caruso, TP, MR Harsch. “Joint Ventures in the Cable and Videotex Industries.” Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1984.

- “Videotex.” In Wikipedia, April 2, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Videotex&oldid=1015693680.

- “WHY MICROSOFT CAN’T STOP LOTUS NOTES – December 12, 1994.” Accessed April 13, 2021. https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1994/12/12/80046/index.htm.

- “VA-MD Vet Med Vital Signs – December 2011.” Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.vetmed.vt.edu/news/vs/dec11/index.asp.

- Robson, B, TP Caruso, and UGJ Balis. Suggestions for a Web Based Universal Exchange and Inference Language for Medicine. Computers in Biology and Medicine. Volume 43(12) 2297-2310, December 2013. http://ow.ly/qDFJv. Accessed November 8, 2013. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.09.010.

- Caruso, TP (coPI-30%), G. Marchionini (PI). Personal Health Information Management Needs and Design for the Elderly. Agency for Health Research & Quality. Total Direct: $1,670,000. Studying the personal health information management needs and preferences of people over 64 years of age and making design recommendations for PHR systems for these individuals. Proposal resubmitted but not funded.